There has been some recent press on the claims of George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, two rare books dealers based in New York, to have discovered William Shakespeare’s own dictionary. What’s more, the claim is based on the extensive annotations in the reference work, John Baret’s Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie (1580), which they bought on Ebay for about $4,000 in 2008.

For the last few years I’ve been documenting ways that modern poets have used dictionaries, mostly the Oxford English Dictionary, and thinking about the implications of this for criticism, so I have an especial interest in this kind of thing, but I think just about anyone would be excited to find a book that had been heavily annotated by the hand of the Bard.

The idea that this book belonged to WS himself is based on two main types of evidence: several doodles of capital “W” and “S” in the margins, and curious correspondences between Baret, the annotator’s additions, and passages in Shakespeare’s plays. For instance, as related in Adam Gopnik’s recent New Yorker article [‘The Poet’s Hand‘, 28 April 2014],

Scholars have puzzled over Hamlet’s lines, “Oh that this too too solid Flesh, should melt, | Thaw, and resolve it selfe into a Dew,” because it’s odd that “resolve” should indicate what happens to something that “melts.” In Baret, “Thawe” is defined specifically as “resolve that which is frozen”–and the annotator has made a clear “mute” annotation beside its suggestive poetic pairing.

There’s more where that came from. The dealers have written a book detailing their case for attribution, and created a website, Shakespeare’s Beehive [alvearie = apiary], where anyone [who registers] can read a high-quality facsimile of the Baret, as well as a transcribed list of the annotations, and a sample chapter of their book, where they discuss the “trailing blank” [click to see original and transcription], the unprinted final page of Baret on which the annotator has scrawled a bunch of French and English words:

Attempts to support, or reject, the conclusion of Shakespeare as annotator may fall most heavily on the evidence left behind on a single page at the back of the book: the annotated trailing blank. The blend of English and French words that are added to this page are so diverse an assortment (a visually random selection by any measure), that to discover such dazzling results in the plays wherein Falstaff appears, seems anything but a coincidence.

Koppelman and Wechsler have put a huge amount of work into their investigations, and I do hope it pays off for them. They’re also to be commended for their openness in reproducing the original book and parts of their own research, making it easy for others to follow in their footsteps (potentially to debunk or to shore up their case). They write:

We encourage honest efforts to extend the trailing blank word play game, using the selections that the annotator commits to that page, to authors apart from Shakespeare, whether of his time, or of any other time. This should allow for an ongoing test to our conclusion that nowhere else will such striking parallels be found and echoes be heard.

From what I’ve read on the site, it appears that there hasn’t been much in the way of algorithmic search and comparison or corpus statistics applied to the attribution question, whether in the “trailing blank wordplay game” or the annotations to entries in the main text of the Alvearie.

It should not be terribly hard to do (though time consuming to do well), and would add a dimension to the work already carried out. The authors do mention their “success in turning up — through the use of Google — an obscure note in a nineteenth-century French edition of Shakespeare’s plays that seems to magically replicate the thought process of the annotator”. If Google can find things, I bet Python can too. I look forward to buying hard and e-book copies of all these publications to try my hand at it.

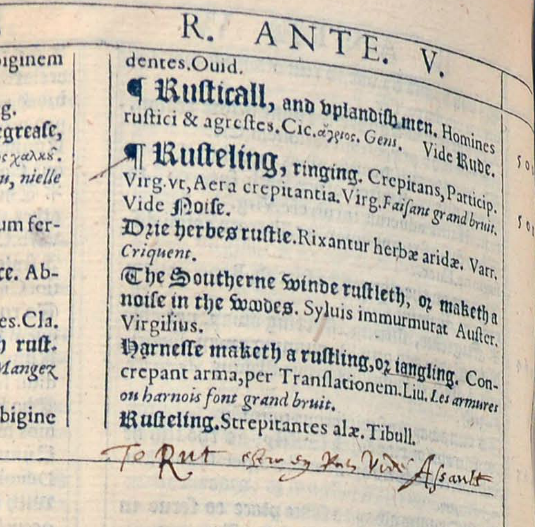

Meanwhile, something for those still convinced that the real author of Shakespeare’s plays is not William Shakespeare but Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland. This from the last page of “R”:

I can’t quite make out the middle part, but the editors have it as: “R501. Rusterling, adds “To Rut vide estre un rut Assault” within text column.

More discussion here:

- Sydney Morning Herald

- ABAA Blog

- Endless Bookshelf Blog

- Forbes

- The Guardian Blog

- Bibliophagist Blog

- Folger Library Blog

- Jason Scott-Warren Blog

- Tweets from Grace Ioppolo

- Vade Mecum Blog

What a momentous event if the dictionary somehow can be proved to be Shakespeare’s…

Indeed! Unlikely to be proved so, perhaps, but fun to try.