Paul Batchelor’s 2012 review essay in the TLS of recent work by Geoffrey Hill and his critics was called “Geoffrey Hill’s measured words”. As many who write on Hill do, Batchelor keyed in to a series of resonant words in Hill’s work, drawing connections between Hill’s poetry and prose via shared terms such as uncouth, anacolouthon, hobby, nobly, etc..

“Measured”, in Batchelor’s title, is ambiguously both “Having a marked rhythm; rhythmical; regular in movement” and “Carefully weighed or calculated; deliberate and restrained”. But Batchelor is also taking the measure of these words and their significance for Hill. Judging poetic and/or allusive significance is a very difficult thing to get a computer to do–it’s hard enough for humans to do well.

But one component of the judging process is fairly straightforward: one thing we measure, often unconsciously, is the relative frequency of particular words in the poetic text vs general language and vs the other poetry we know. Anacolouthon can stand out as an odd word to see in two different Hill texts because it’s not a word you’d expect to see anywhere; in, at, and the show up much more often in Hill than most other words he uses, but they are common enough not to be remarkable.

Those are extreme examples of commonness and uncommonness. Would hobby strike you as an unusual or an unremarkable word? The vast middle is murky, and our intuitions and perceptions don’t always line up with the evidence. The problem is complicated somewhat by genre: some words aren’t very common in speech but show up fairly frequently in poetry, and vice versa.

So, bearing in mind the many times I’ve heard Hill complain that critics treat his work as if it were written on graph paper, I thought it might be an idea to make good that complaint. Below is a digital exploration in graphs of Hill’s poetic diction.

First a note on methodology. Skip the next two paragraphs if you’re not interested in these details.

My corpus of Hill’s words is all the poems published before Broken Hierarchies, (i.e. up to Odi Barbare) in their original forms. My comparison corpora are the British National Corpus or BNC (100 million wds) and a large corpus of 20thC poetry (11 million wds). The process involves getting the frequencies (per million) of Hill’s lexicon for all three corpora, and comparing them to each other. In order to keep results relevant, the most frequent words are filtered out (prepositions, articles, etc.). Also, a stemming algorithm removes word endings, in order to count word forms together. This isn’t perfect–certain word forms aren’t recognized (it groups sexes and sex, but leaves out sexual) and, less often, it reduces different words to the same stem. And of course it’s no good with homographs. But on the whole, it’s preferable to plotting, e.g., all singular nouns apart from their plurals.

For every word stem in Hill, a frequency per million words is obtained for the Hill, BNC, and poetry corpora. Then a measure of relative frequency is obtained for the frequency in Hill vs the frequencies in the other two corpora [the measure here is 100*log(f1/f2)]. Higher numbers mean that Hill uses the word more frequently than it appears in the control corpus. Words that don’t appear in those corpora are assigned an arbitrary value of 400.

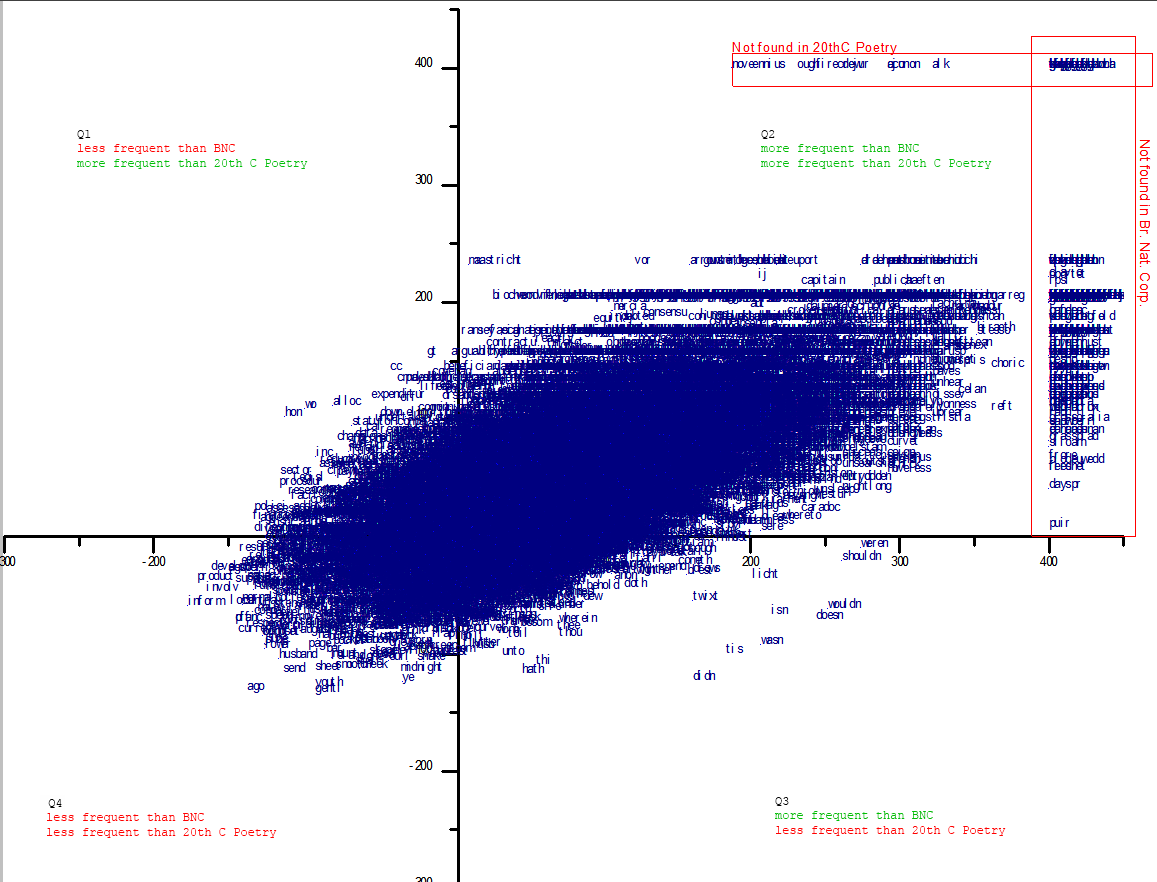

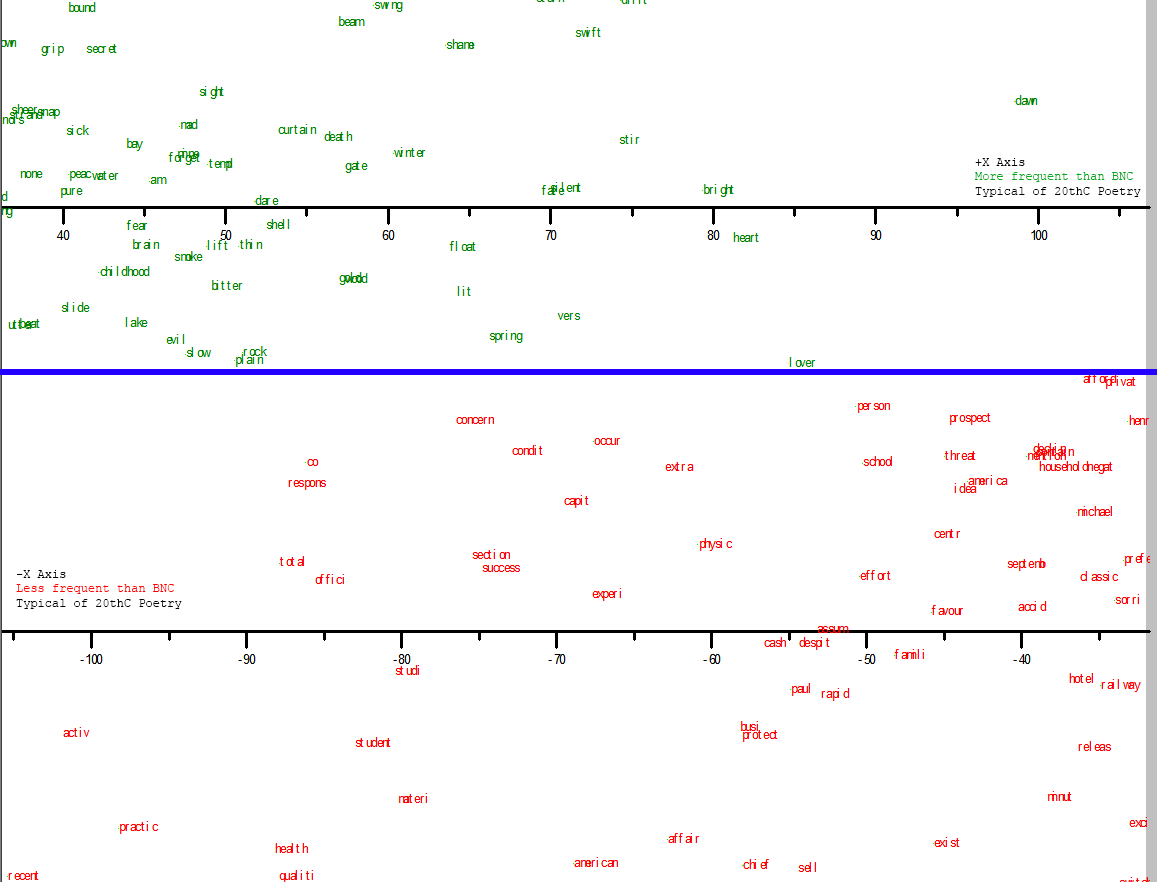

Okay. The first chart is all of Hill’s words, plotted according to their relative frequencies vs. BNC (x-axis) and 20thC poetry (y-axis). This means that the higher the plot on the y-axis, the more more-frequently Hill uses the word, compared to most 20thC poetry. The farther right, the more more-frequently Hill uses the word than you would expect to see it in the BNC, which here stands in for “common usage”. We’re looking at a log measure, remember, so a 100 on the axis means that the word occurs 10x more frequently in Hill than in the control corpus, whereas a 200 means it occurs 100x more frequently in Hill, and 300 = 1000x. [Click image to make large]

Obviously there are too many data points here to say very much that’s meaningful about the corpus. We might remark on the general shape, with many more words stretched out to the corner in Quadrant 2 (Q2), many fewer in Q4 (and these bunched closer to the origin), and even fewer in Q1 an Q3. Even as a ‘footprint’ or general shape this might be compared to other authors later, or other genres by the same author, etc.. The radical outliers–those boxed in red–are also a part of this general shape.

Having shelved the idea of the comparative footprint for the time being, [update-have since posted some preliminary work on this] first I’d want to check out these radical outliers. They will tend to be foreign words, neologisms, or digitization errors: examples on this plot include oraclau, firecrew, brpken, celfyddyd, wrinching, google [BNC predates Google].

Perhaps more interesting are the less radical outliers. For instance, the word ago occurs about 20x less frequently in Hill than in either control corpus [note this implies it occurs roughly equally in each control corpus] (Q4). Expenditure and sector get used by Hill a lot more than most poetry uses them, but a lot less than they turn up in the general corpus (Q1). Words Hill uses much more frequently than they occur in either corpus (Q2) include choric and reft. The contractions in Q3 are interesting. They may be text normalization errors – note to self to investigate.

If some of these findings are suggestive, it suggests that we might inspect such areas more closely. One way to do this is would be to zoom in on this graph. But we might also do better if we started by applying an additional filter beforehand. Choric and reft, like anacolouthon, are such unusual words that we hardly need a graph to tell us that Hill is over-employing them, statistically speaking. [Though it would still be worth looking at a list of very rare words which show up more than two or three times in Hill – but that’s a different kind of investigation than I have in mind for now].

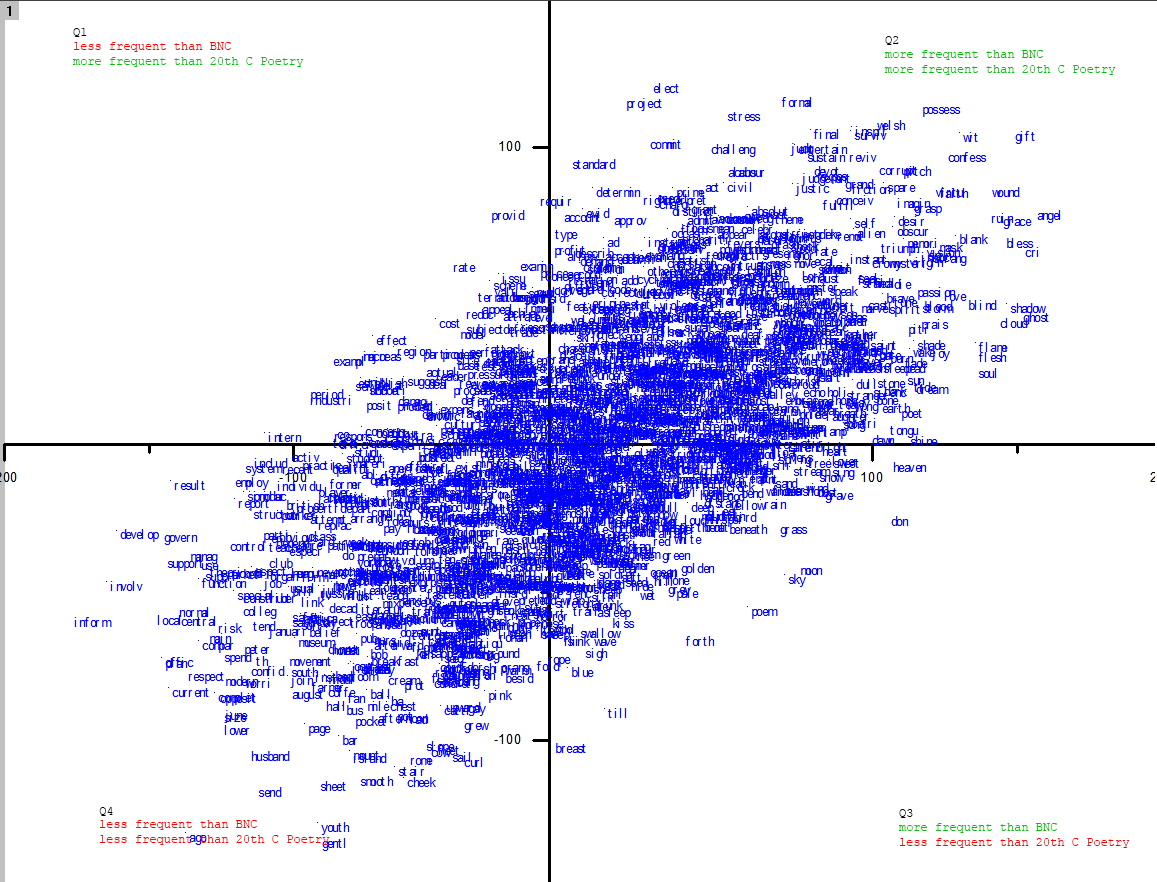

So below I’ve taken the same data, but I’ve removed all stems with frequencies less than 50 wds per million in either BNC or Poetry. 50 wpm is an arbitrary threshold: it is the frequency of words such as chop, laughter, or summon in the BNC; in the poetic corpus repair, proceed and afford occur at about that rate. Anything rarer than that is eliminated, which reduces considerably the field:

This starts to look a lot more interesting. The outliers in Q3, those that Hill uses much more frequently than common speech but much less frequently than contemporary poetry, include breast, forth, poem, sky, moon, and heaven. At the extreme of Q4, words that are far more frequent in common and poetic speech than they are in Hill, we find husband, inform, cheek, ago, youth, respect, sheet, current, develop, govern. At the other end, words that Hill favours disproportionately, we have, among many others, elect, civil, formal, possess, gift, angel, confess, blank, blind, wound, wit, pitch, corrupt, entertain.

If you know something about Hill’s poetic preoccupations, these findings will not surprise you. Or some will and some won’t. But seeing what you already know or think you know displayed in an unfamiliar way is not a trivial kind of confirmation. Our intuitions about commonness, not to mention relative commonness, are often wrong or imprecise, and I don’t think it’s a waste of time to subject them to empirical tests. When Broken Hierarchies was announced last year, the title words had little resonance for me, so I went searching for similar indices of their importance.

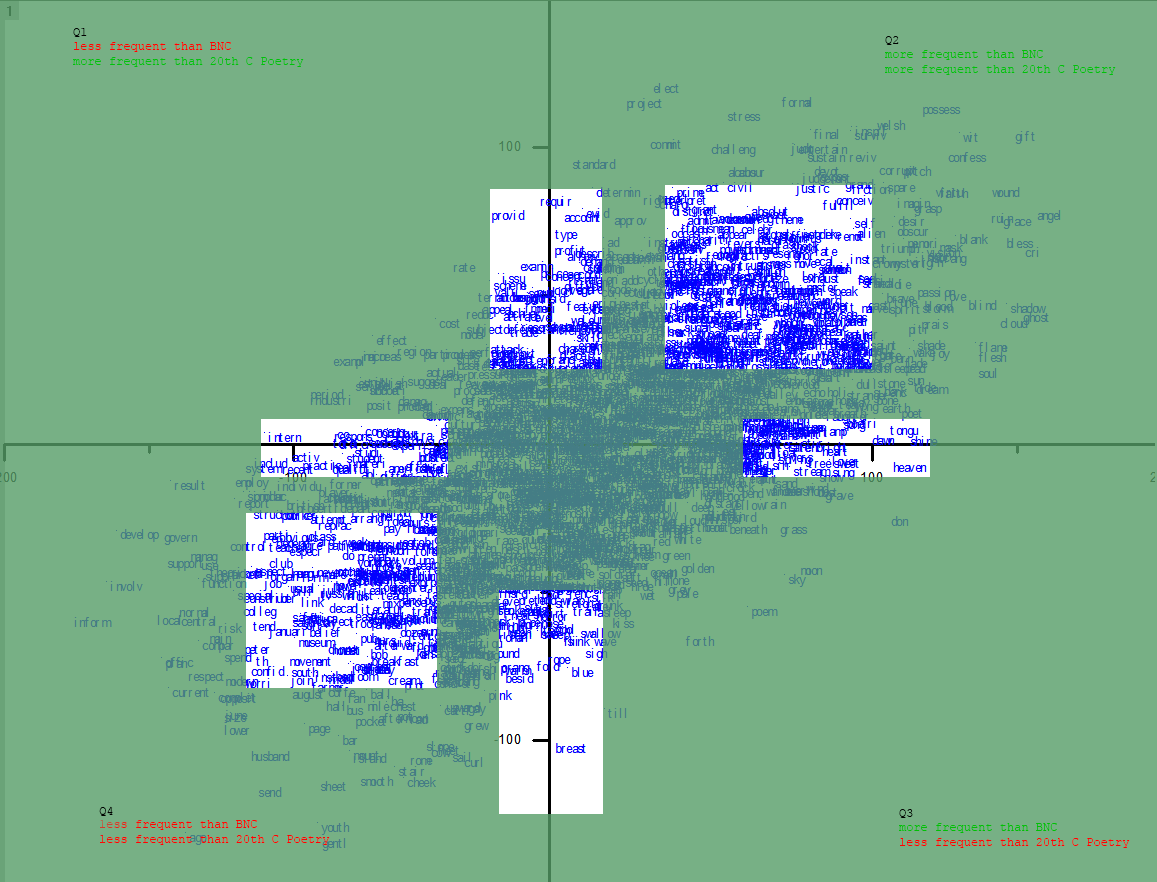

If you don’t know much about Hill’s poetic preoccupations, (and even if you do) I think exploring this graph might give you a few things to think about. I for one would take a much closer look at the top corner of Q2 and the bottom of Q4, as well as the ends of each axis, e.g these parts, roughly:

So here are a few close-ups for inspection. Click the images to biggen them. Bear in mind that the labels are stems, not words, so you may have to extrapolate, e.g., the stem ignor, to the set of words [ignore, ignores, ignored, ignoring, ignorance, ignorant]. Let me know in the comments if you find anything interesting:

Most statistically overrepresented word stems (top Q2):

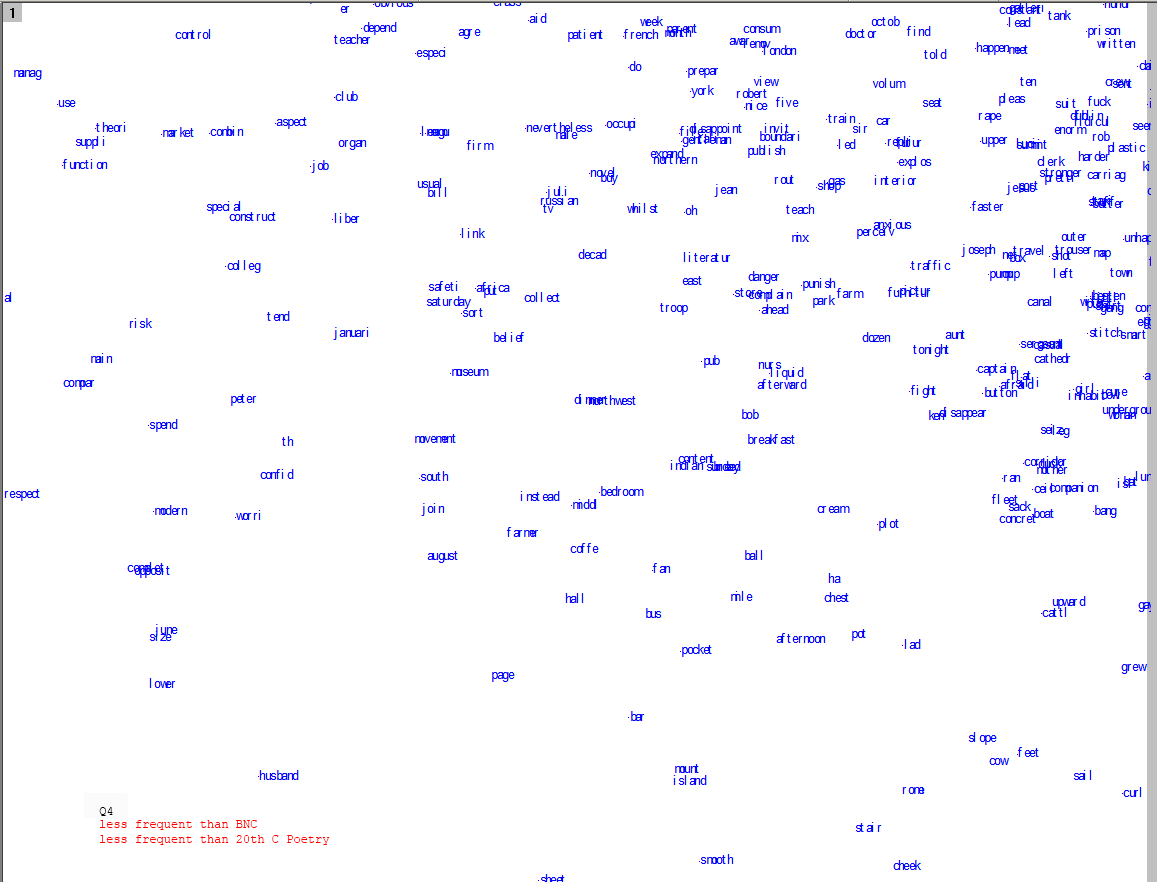

Most statistically under-represented word stems (bottom Q4):

Most over- and under-represented compared to common usage, but typical of 20thC poetry:

Most over- and under represented compared to 20th C poetry, but typical of common usage:

[…] This afternoon I came across a blog post on the digital humanities by David-Antoine Williams: MEASURED WORDS […]

[The post that tracked back is short enough that I’ll recopy it below. See the original here -D-AW]

This afternoon I came across a blog post on the digital humanities by David-Antoine Williams: MEASURED WORDS

I want to read the post more carefully, but I was drawn by the pretty graphs and my abiding interest in the lapidary poems of Geoffrey Hill. (I can still picture him glowering at me from the end of the seminar table, commanding the room with his agony of spirit) At first glance, I am struck by its resemblance in method and tenor to Andrew Piper’s recent campus talk in which he analyzed the diction of Goethe’s corpus.

For my part, I’m interested in the extent to which these studies locate their significance in the weight of the visual. Both Piper (take my word for it) and Williams display a marked rhetorical restraint. Consider, for instance, the following claim, itself an example of “measured words.” Williams writes:

“If you know something about Hill’s poetic preoccupations, these findings will not surprise you. Or some will and some won’t. But seeing what you already know or think you know displayed in an unfamiliar way is not a trivial kind of confirmation. Our intuitions about commonness, not to mention relative commonness, are often wrong or imprecise, and I don’t think it’s a waste of time to subject them to empirical tests.”

The possibility of “seeing what you know,” I have to admit, is seductive for intellectuals who prize knowledge as much as we do. But then again, I don’t want to be seduced too easily (what fun would that be?). And the seemingly offhand “I don’t think it’s a waste of time” belies the huge number of resources—all of those forms of time–required to run such a study. As an understatement, the phrase seems to draw a lot of attention to itself, and begins to shade into false humility.

All for now…

A very interesting point about the rhetoric of this, and other similar attempts. It’s partially the rhetoric that gets us from the positivism of dataset metrics to the making of insightful literary criticism, I believe, so I want to be careful about the claims I make.

I’m not aiming for modesty, however, with the comment you cite. In adopting a defensive posture there I’m trying to anticipate the most likely objection-one which I’ve levied against similar attempts myself-which is that there’s not much to be learned from such efforts. If you know the opus well, they won’t show you anything new; and if you don’t know the opus well, you won’t have the means of interpreting the results. But I think there is something to be learned, and I think it has to do with the intellectual activity of bridging the outcomes of digital methods with the questions of criticism.

Certainly I wasn’t implying that this didn’t take me a long time to do. Not playing Eliot’s possum: “No honest poet can ever feel quite sure about the permanent value of what he has written: he may have wasted his time and messed up his life for nothing”.

[…] counting things in literary works or big corpora to inform analysis. I have even done it myself (here, here, here, and plenty elsewhere), in a much less sophisticated way than Dalvean does. But […]