I’ve recently been tracing out the history of a relation between two particular ideas in English culture, which I would call a metaphorical relation: one idea being described in terms of the other. In tracing it back, I’ve noticed that in the 19thC texts I’m reading, it is only rarely referred to as a metaphor — the more usual term is analogy.

That got me to wondering about the usage history of metaphor, in technical as well as common parlance. First stop: OED, which provides this wonderful first quotation, from the Ordinal of Alchemy (c.1477). Here’s the poem in fuller context (with the part quoted in OED underlined):

The subtile science of holi alchymye;

Of which science here I entende to wirte,

[…]

Though that I write in playn and homely wise,

No good man shulde such writing despyce.

Al mastirs which write of this soleyne werke,

Thei made theire bokis to many men ful derk,

In poyses, parabols, & in methaphoris alle-so,

Which to scolers causith peyne and wo;

So it appears the word is first borrowed into English writing as a somewhat technical or prosodic term, but one describing abstruse and obscurantist scientific writing (albeit in verse). This poet, Thomas Norton (also a customs controller, like Chaucer, whose Franklin is apparently a model), won’t burden us with such poyses, he says (in couplets).

Analogy has a much more convoluted history. It starts out in English as a mathematical term, an “agreement of ratios” (in use sporadically from 1425-1855). Other usages marked obsolete mean “correlation, harmony, agreement” and “A figure of speech involving a comparison, a simile, a metaphor”, with citations from 1536-1787. The prevalent current sense, a “Correspondence between two things, or in the relationship between two things and their respective attributes; parallelism, equivalence, or an instance of this” begins to be used in the mid 16thC.

Now you might think that “comparison” and “correspondence” are similar types of relationship, but they’re not exactly the same, as the splitting out of definitions implies.

So, regarding this particular metaphor that I’ve been tracing (what is being compared isn’t important and would confuse things there), which in the 19thC was more likely to be described as an analogy, these are the possibilities in that occur to me: (1) perhaps the understanding of the relation between the the two ideas has changed between then and now–it could be that it was once understood as a correspondence, and now is understood as a (mere) comparison; (2) OED could be splitting senses too finely, and/or (3) the senses may have merged somewhat in very recent use, or (4) OED has missed samples of 18thC uses of the “metaphor” sense of analogy, perhaps like the ones I’ve come across.

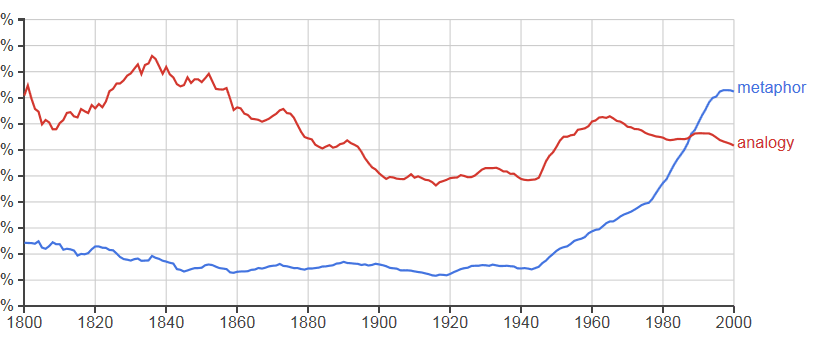

In any case, Google Books n-gram viewer gives an interesting picture of the relative incidence of metaphor vs. analogy:

It’s worth noting a (relatively) recent extension of metaphor from the technical label for a figure of speech to something closer the current sense of symbol. This sense, which OED defines as “Something regarded as representative or suggestive of something else, esp. as a material emblem of an abstract quality, condition, notion, etc.” is inaugurated by Emerson, in Nature (1836):

Parts of speech are metaphors because the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind.

Sure, the surge in metaphor doesn’t start till 1940, at least according to the Google corpus, which has many flaws that might skew this graph. However, it stands to reason that terms that get extended from technical applications to general usage would increase in overall frequency, and that this effect might take some time to set into a corpus of published works.

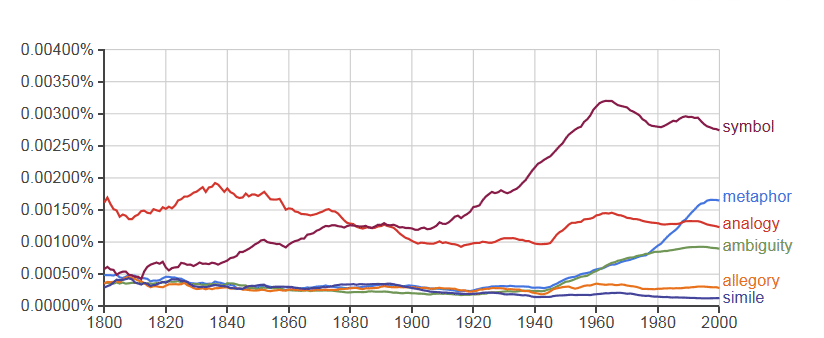

So I thought I would put the analogy/metaphor chart in the context of how some of the other “correspondence” terms that I need to explain in my poetry classes have fared, relative to each other, in the Google corpus over the last 200 years. The graph is neat:

Although all the non-allegory words start about the same, the graph shows that over time symbol is the clear winner in the group. It starts to surge earlier, overtakes analogy sooner, and rides highest of all into the current millennium. What I take to be the overriding current sense of the term–“Something that stands for, represents, or denotes something else”–is as old as Spenser (1590): “That as a sacred Symbole it [sc. a blood-stain] may dwell In her sonnes flesh.” This is an extension of a purely religious sense, “A formal authoritative statement or summary of the religious belief of the Christian church”. There is another sense of symbol, of course, a “written character or mark used to represent something; a letter, figure, or sign” which gets used rather a lot in mathematical and scientific texts, and may well be influencing the curve.

I would love to better understand how and why metaphor and symbol emerge in this corpus, while analogy submerges, and allegory and simile do nothing at all. I think the factors are, on the one hand, the generic composition of the corpus over time, and on the other, real changes in the vocabularies of different genres of text.

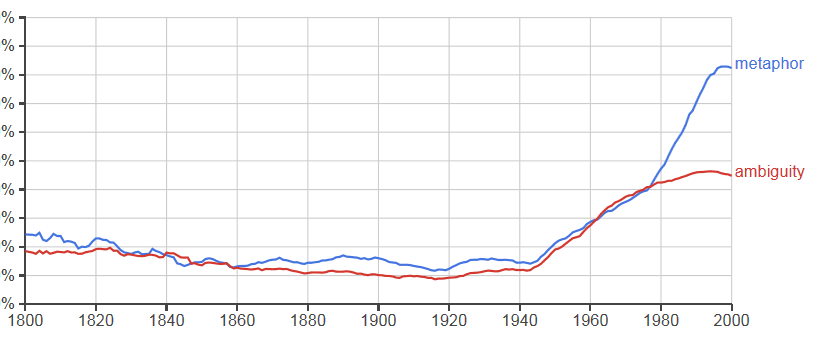

On these axes of investigation, the case of ambiguity vs metaphor presents an interesting case study:

I can’t conclude anything by this, since (again) the make-up of the corpus is opaque, but it does seem rather incredible that the two terms track each other so closely until about 1980, including at the exact moment of surge at 1942 or 1943. William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity was first published in 1930, which is ample time for it to have contributed something to this uptick of ambiguity in literary criticism. But how much of the corpus in each decade is literary criticism … or reprints of literary criticism? We don’t know, but we’d like to. It would help to make sense of all these graphs, and might explain the divergence at about 1980 in the final one.

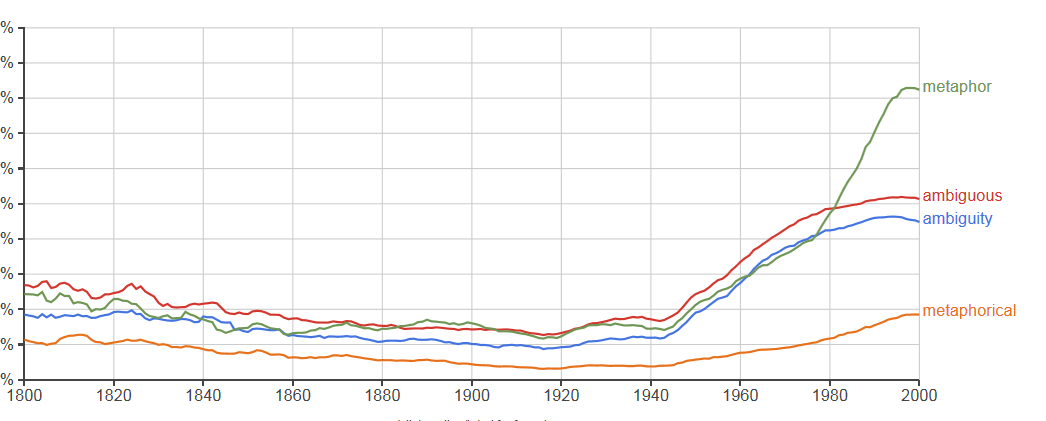

Yet, the pictures we get from Google always make you think. One way to test my hunch about the variation in the generic make-up of the corpus might be to test related word forms. If, let’s say, a bunch of Empsonian books went through a load of editions, that would presumably affect ambiguous in the same way as it affects ambiguity. And if the parallel surge of ambiguity/metaphor were attributable to an oversampling of literary criticism, then metaphor/metaphorical would follow an analogous (not metaphorical) path to ambiguity/ambiguous. But look:

More data, more questions. There is clearly something happening around 1942, and clearly metaphor is different from the rest of these words, even closely related words. But the how and why is not yet clear, at least to me

[…] (derived from the Greek “metepherein”, meaning “to change over”) was in Thomas Norton’s The Ordinal of Alchemy in […]