Gotthold Lessing is credited (among other things) with pointing out that it’s weird for Classical writers to describe the art of poetry in terms of the visual arts, since poetry happens sequentially in time, and painting happens statically in space. But Lessing is wrong, or at least overly categorical. Before a word is read, a poem (unlike a novel) almost always occurs first as the image of a static shape on a page. In this post I’m going to look at a poem–literally–in different ways, partially to test out what computer-assisted visualizations can tell us about a poem, and whether these correspond to, or maybe even exceed, our unaided experience of it.

Hopkins’s poem “The Windhover” is a favourite of mine. I’ve reproduced it below. Instead of scrolling though as you read, scroll until it is complete on the screen, as it would be on a page. Then, before reading, spend 10 or 20 seconds just looking at it:

The Windhover

To Christ our Lord

Don’t read it yet. There are, as always, lots of ways of experiencing the poem, and several aspects to any one experience of it. One important way I think you can experience a poem, at least as first, is as a spatial whole. Glancing over it–as you would a painting–you can glean a lot of information about how the poem is constructed, even before a sound has been produced, and this information will condition your expectations (acoustic and conceptual) and therefore your experience as you read it through sequentially. You can see at a glance, for example, that the first eight lines will rhyme (which is unusual … maybe you also see a difference in the way those -ing words rhyme) and you might notice the rare ‘-illion’ rhymes (how many other -illon words do you know … and do you even know ‘sillion’?) sticking out beyond their predecessors on lines 10, 12, and 14. At this point, if the lineation and squareish shape didn’t tip you off at the outset, you’ve identified the poem as a sonnet, which leads you to form certain working hypotheses about how those last six lines will relate conceptually to the first eight. Several sets of repeated letters within the poem might also catch your eye, leading you to think that alliteration and assonance, in addition to persistent rhyme, will be prominent formal features.

Okay, now read it. Hopefully you’re reading aloud, and before you’re halfway through the second line your mouth is filling with consonants, each jostling another for a shot at its proper place of articulation. Or, maybe you’re familiar with the text and you’ve practised it. Maybe you sound like the guy in this recording, which I pulled off Youtube:

It’s these three lines I want to look at, literally, in a couple of different ways. The first is the way we normally look at poems, which is as words encoded on paper or on a screen, in the Latin alphabet according to an established orthography:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his ridingOf the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

If you’re like me, what stands out at first is repeated letters, and repeated letter clusters. The entire word ‘morning’ occurs twice in the first line, ‘-in’ pops up eight times, including within six instances of ‘ing’. The first line’s three ‘m-‘ words are outdone by the six ‘d-‘ words in the second line. Line two also echoes the three ‘consonant-vowel-n’ type syllables in line one (‘morn-‘, ‘morn-‘, ‘-ion’; keep it non-rhotic) with four of its own (‘-phin’, ‘dawn’, ‘drawn’ and ‘-con’).

I’m a scribbler, and this is the kind of thing I tend to scribble on poems:

This helps me to see what I’m hearing, to diagram or at least highlight and keep track of the sound structure, but obviously it depends to some degree on having the alphabet encode the sounds for me, and there are some notorious quirks in the way it does this. I hear it in my head, or out loud, as I read, but I’m marking it visually on the paper, just as I’m using my eyes to see which sounds ought to follow which. Only (unlike Geoffrey Hill) I don’t actually own a multicoloured pen.

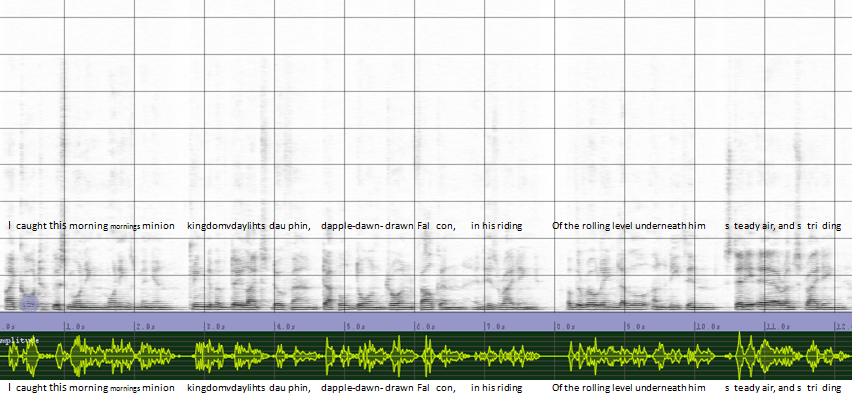

What if there were other ways of looking at these lines? What if we looked at, for instance, a spectrogram of the sounds someone made when reading it, say the person recorded above. The first lines would look like this [click image for size]:

This way of looking at the poem gives us information that is missing when looking at the written version. For one, it accurately represents the time it takes to pronounce each sound and each word, and the volume of each sound that is being produced, also over time. This means, among other things, that the spectrogram is a much better way of visualizing rhythm and cadence. The stressed syllables in the poem will generally correspond to places where a chunk of amplitude (bottom graph, in green) is thicker and wider than the area surrounding it. And you can see silence in this graph, which you can’t see in the written poem. You can see where (when!) words are pronounced in a string of uninterrupted sound, and where there’s a hiatus between word boundaries. You can also see which parts of words take up relatively less acoustic space, and which more.

You can even, with a little practice, identify areas of similar sounding sounds, such as when, in the frequency pane (above, top graph), the bars go way up – those are ‘s’ and ‘f’ sounds – very high frequency – or, looking a little closer at the first few seconds:

Here we can see a similarity in the shape of the curve for each instance of ‘morning’ (and also a slight difference between the two), plus we can see how the ‘k’s of ‘caught’ and ‘kingdom, the ‘d’ of ‘daylight’s’, and, to a lesser extent, the two ‘m’s of ‘morning’/’mornings’ form a clearly defined left side boundary. There’s an acoustic reason why alliteration on ‘t’, ‘k’, ‘p’, ‘d’, ‘g’, and ‘b’ is perceived as choppy. And here’s the visual representation of that.

But while the spectrogram is good for rhythm, and good for visualizing sound happening in actual time, it isn’t really that great at showing alliteration, at least not cases subtler than those obvious choppy bits, and not without a lot of practice. There’s just too much acoustic information present there, which creates ‘noise’ (the pun is unavoidable – try to ignore it).

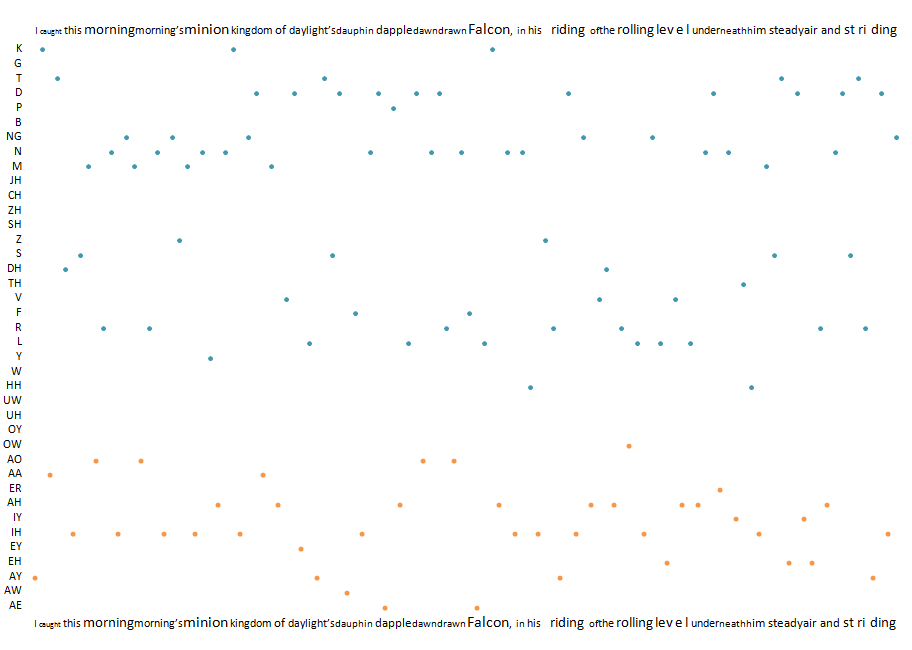

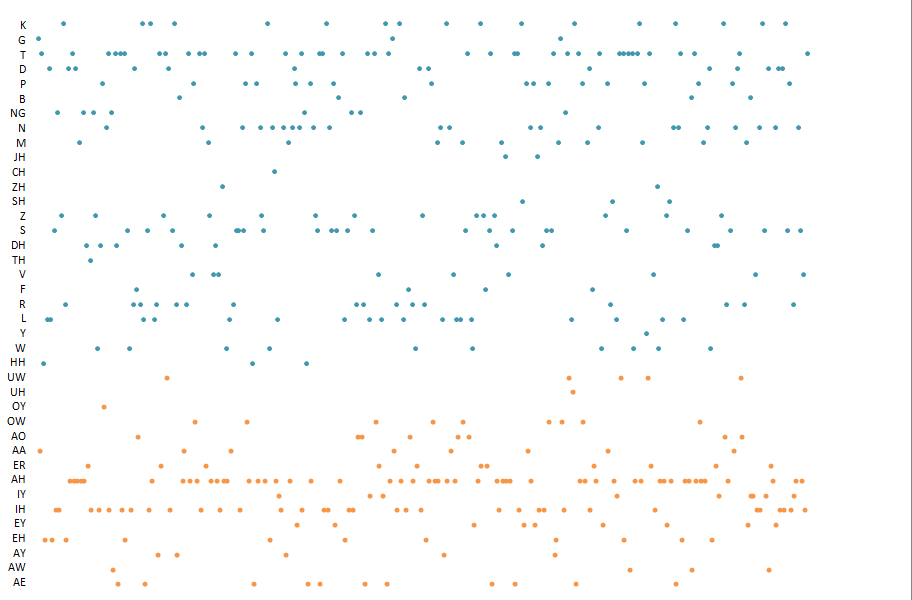

Here’s another way of visualizing alliteration that simplifies the available information quite a bit. I used the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary to replace the orthographic encoding of the poem with a phonemic code, and then ordered the 39 phonemes along the Y axis, with vowels all at the bottom and consonants at the top, trying to keep like sounds together (for consonants, by separating fricatives from stops and grouping them by place of articulation – vowels are trickier, due to the idiosyncrasies of CMU’s system). Then I mapped the sounds in sequence along the X axis, to produce this graph [click for size]:

This graph could do better in approximating actual time (by giving vowels twice the horizontal space, eg. – I’ll work on it). But it shows areas of sequential consonantal similarity–that’s called alliteration–pretty well. There’s a dense group of nasals (‘m’,’n’,’eng’) first, followed by a series of dentals (‘d’, chiefly), and then more nasals (all ‘n’). Closer to the end there’s another set of nasals followed by another set of dentals, alternating between ‘t’ and ‘d’, which I hadn’t noticed when I did my scribble (it happens).

What this graph shows nicely, and what is hard to see in the text scribble and harder still in the spectrograph, is how these alliterative regions overlap with one another. This is also difficult to detect and keep track of when saying or hearing the poem, since you can only say or hear one sound at a time. It’s apparent in the graph though that the first ‘d’ group begins before the first nasal group has ended, and ends after the second nasal group has started. And, above this on the chart, we can see that a much thinner alliteration on ‘k’ has been taking place all along, at long intervals, on ‘caught’, ‘king-‘, and ‘-con’. We also see that between the triple ‘l’ group in ‘rolling level’ (CMU doesn’t distinguish light and dark ‘l’ — do you, when thinking about alliteration?) and the last group of dentals, the alliterative texture thins out quite a bit.

One thing the graph less good at is showing consonant cluster alliteration when the cluster is made up of dissimilar sounds, like the ‘steady’/’striding’ group near the end. You can see the t-d, t-d easily, but because ‘s’ is plotted lower, it’s hard to see that it’s part of the onset in both words, that the alliterative pattern is better thought of as st-d, st-d. Lines linking up sequential consonants might help to see this.

Here’s what the whole poem looks like. Like Finnegans Wake in Braille? Or revealing something about acoustic structure? See what you think:

And here, for comparison’s sake, is the first paragraph of this post (on the same X scale):

Now I want to revise my opening paragraph. But I can’t, because I’ve already made the graph.

No Comments