I’ve always felt it was a peculiar kind of luck to live in the same times as many of the poets I read, and write on. Of course there’s the great luxury of hearing the poet “live” (what was Keats’s voice?)–but really what I’m most grateful for is to be able to look forward to new writing, to developments in style and thought, to more surprise and more poetry. A corpus need not be a corpse.

But as long as a poet is still writing, revisions to already published works may also occur, and this can pose some problems for the crrrritic. Geoffrey Hill’s Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012, still a month away from print availability, has shown up in searchable form on Amazon [cf. Hill’s unknowing “I do not go online in any way”]. Taking a peek around it, I’m stunned by the amount of revision that has taken place, especially in the more recent work.

Here, for instance, is a poem that has already attracted a fair bit of critical attention since it was first published in Scenes from Comus (2005), presented in form it took in that collection:

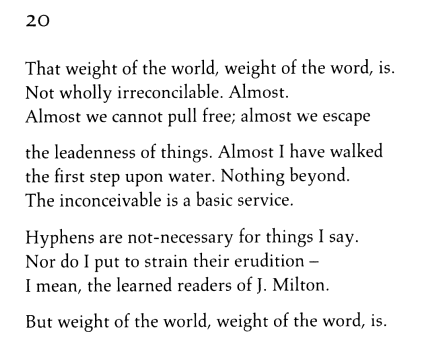

And here it is in the coming “collected”, with all the claims to definitiveness that category of publication implies:

And here it is in the coming “collected”, with all the claims to definitiveness that category of publication implies: Wait, what? I’ll leave alone the question of which version is better. These are two completely different poems. The changes neatly demonstrate the distance between a semicolon and a period, between “But” and “And”, and crucially between “word” and “world.” And the inversion of the two terms in the final line may be a good illustration of the poem’s central proposition, but putting it this way changes everything about the philosophical development of the idea within the poem.

Wait, what? I’ll leave alone the question of which version is better. These are two completely different poems. The changes neatly demonstrate the distance between a semicolon and a period, between “But” and “And”, and crucially between “word” and “world.” And the inversion of the two terms in the final line may be a good illustration of the poem’s central proposition, but putting it this way changes everything about the philosophical development of the idea within the poem.

Then there’s line seven, originally an almost self-cancelling statement about hyphenation, which has been taken out completely. The original poem makes what Christopher Ricks thinks (correctly, I believe) is a not-so-veiled riposte to Ricks’s early essay on Hill’s hyphenation (see Ricks’s Force of Poetry for that essay, and True Friendshipfor the discussion of Hill’s late poem). Maybe Hill didn’t like Ricks’s rejoinder. If so, removing the line altogether seems a petulant final word on the matter, a wilful withdrawal from conversation and refusal of friendship.

What is Ricks to do about this, having now written on an apparently obsolete poem (in two books — see also his chapter in Lyon & McDonald)? He can’t revise his own critical work — the object of criticism has been in some way withdrawn. And what about others who have written on the original poem: what about me, hey, and Piers Pennington, and Michael O’Neill, and Peter Pegnall, and Charles Lock, and others? And what about future writers? Are we all bound not only to acknowledge the revision, but also to acknowledge the supremacy of the revision? And will Hill criticism have to endure a long period of deadening debate over the relative authority of the different versions and editions of the poems? And is this, in fact, the last word on all the poems 1952-2012, or should we expect corrections and revisions in the next printing?

Now, the evaluative question I’m avoiding is one on which Hill himself has had some sharp things to say, in a conversation with Peter McDonald [link] about poets revising their own work in later life. He asks Hill at the outset about good poets who have been consistent or prolific self-revisers. Hill says: “I can think off the top of my head of two or three. And all of them disastrous.” J. C. Ransom, W. H. Auden, and M. Moore were all “disastrous” in their late self-revisions, and in each case the revisions were “monstrous misjudgements” borne of “entirely unnecessary guilt,” and so moral as well as aesthetic failures. W. B. Yeats, though, “can be applauded on some but not all of his rewritings,” Hill says. “Reconceived, rethought, rewritten” is how McDonald characterizes Yeats’s late changes.

Section “20” of Comus certainly has been reconceived, rethought and rewritten in Broken Hierarchies, and my quick look through the Amazon text shows plenty of other major and minor changes in places both expected and unexpected. Is a variorum edition on the cards? Broken Hierarchies is already almost one thousand pages long. A thousand. Is this defiance or a dare?

I think the Scenes from Comus version is the stronger of the two. Tho I’m sure I’ll regard some of the other revisions in Broken Hierarchies as being improvements over the original versions.

“Urge to unmake all wrought finalities”

I would agree: the original version is stronger. Makes me a little uneasy to see what else is different in the book. That said, the extended version of “Hymns to Our Lady of Chartres” looks very interesting, from what can be seen at Amazon….

I’m pointed to another, pre-BH call for “a variorum edition of the poems of Geoffrey Hill, epigraphs included and, where excluded, with each absence meticulously registered,” in this: http://www.connotations.uni-tuebingen.de/lock0222.htm by the same Charles Lock I mention above.

I was fascinated to come across your highlighting the significant changes to the Weight of the world. This morning I was comparing the Pindarics and found very extensive changes and loss.

Geoffrey Hill: Without Title pp33-55 Numbers 1 (24), 2 (3), 7 (16), 9 (6), 10 (11), 14 (16), 19 (13), 20 (20), 21 (5) are incorporated into the Broken Hierarchies set of 24 Pindarics, but the epigraphs taken from Cesare Pavese’s Diaries are excluded. No’s 3,4,5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 15.16, 18 have vanished altogether from both volumes. There is no editorial explanation for such a major alteration.

Any comments would be appreciated especially as to why the epigraphs should have been cut.